By Carl Rieckmann

Big Horn County News

June 19, 2003

|

By Carl Rieckmann Big Horn County News |

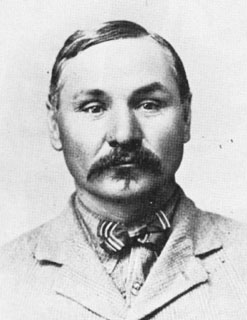

Coming to rest at the place of arguably his greatest

victory, it’s the dignified, dogged and melancholy countenance of Sioux Chief

Crazy Horse – one of George Armstrong Custer’s worst, and last, nightmares

– that quietly threatens from the small 1877 tintype, say historical experts

who offer evidence they assert proves the mysterious portrait to be the only

known likeness of the famed warrior-chief.

“We believe, frankly, that we’ve proven it’s Crazy

Horse,” says the tintype’s owner, James (Putt) Thompson, chief curator of

the Custer Battlefield Museum at Garryowen, who purchased it about a year ago

and has received collaborating support from modern technology and the tenacious

historical legwork of an Italian immigrant, as well as from an evidentiary path

of the tintype’s origins.

While the original tintype of the long-disputed photograph

will be on loan for museum display, the mysterious controversy over whether it

really is Crazy Horse after an earlier historical presumption that the chief

never allowed his picture to be taken undoubtedly will continue to cloak it.

“Mystery breeds out here at the battlefield,” chuckles

Thompson, in reference to the countless Custer theories, legends and myths that

abound from the world’s probably most discussed and second-guessed battle.

Pietro Abiuso, a 47-year-old Italian who came to America at

age 23 and has spent another 23 years researching Crazy Horse, believes he has

nailed down a number of important details from original historical archival

sources to prove the chief posed for the rare photograph shortly before he was

murdered by Army hands.

“From top to bottom, I’ve got all the descriptions,

from bottom to top,” he emphasizes.

Thompson points out a major problem has been the flat

pronouncement of historical writer Mari Sandoz, in her 1942-published biography

“Crazy Horse: The Strange Man of the Oglala,” that “(t)here never was a

photograph taken or a likeness made from firsthand witness of Crazy Horse.”

Little reason seemed to exist to doubt her.

“Everyone believed it and took it as the truth, and it

wasn’t,” notes Thompson. “She created a myth.”

The portrait is what’s known as a quarter tintype,

2.5-by-3.5 inches and one of four images on a plate, and was taken at Fort

Robinson, in the summer of 1877, Crazy Horse’s 35th and final year.

And its first owner was Baptiste (Little Bat) Garnier,  a

highly regarded Army scout of French and Sioux parentage who was considered to

be a good and trusted friend of Crazy Horse.

a

highly regarded Army scout of French and Sioux parentage who was considered to

be a good and trusted friend of Crazy Horse.

It’s presumed Little Bat persuaded the chief to have his

picture taken with assurance that it would be kept secret while he still was

alive.

“Once he saw his image on this metal, he said, ‘Don’t

take it around,’” observes Thompson. “He

had a lot of enemies, and there was a price on his head.”

Thompson and others debunk the theory advanced by some

writers that Crazy Horse was afraid of cameras as a “shadow catcher.”

Denis McLoughlin, who in 1975 published “Wild and Woolly:

An Encyclopedia of the Old West,” reported that Dr. Valentine T. McGillicuddy,

as Crazy Horse was dying after being bayoneted at Fort Robinson on Sept. 5,

1877, tried to take the chief’s photograph but that the Indian turned to the

wall and said “no one must take away his shadow.”

“Writers have used this incident to prove that Crazy

Horse never allowed his photograph to be taken, but this, of course, is

ridiculous,” McLoughlin said in a footnote.

“Crazy Horse was dying, and to an Indian ‘in

extremis’ his ‘shadow’ would be something tangible, a very hold on

existence; therefore, the McGillicuddy incident only proves that the war chief

did not want his photograph taken under the circumstances related. If this

assumption is correct, then one of the half-dozen or so photographs going the

rounds that are alleged to be of Crazy Horse may be a likeness of him.”

When Little Bat was murdered in 1900 at Crawford, Neb.,

near Fort Robinson by James Haguewood, the tintype became the possession of his

wife, Julie Mousseau, a second cousin of Crazy Horse. Upon her death, it went to

her daughter, Ella, who became known as Mrs. Ellen Howard.

When acquired by Fred Hackett, it was accompanied by a signed letter from

Mrs. Howard, witnessed by Hackett and C. Bear Robe, attesting to the tintype’s

authenticity.

Hackett joined with J.W. Vaughn to publish the tintype’s

image, for the first time, in “With Crook at the Rosebud” in 1956.

Then, Carroll Friswold obtained the tintype from Hackett, along with the

Howard letter, and used it in a collaborative effort with Robert A. Clark in

publishing “The Killing of Chief Crazy Horse.”

And, while dispute hung around the image in the aftermath

of these publications, Abiuso, the historical sleuth, was instrumental in

unearthing the original tintype and Howard letter in the effects of Friswold’s

estate.

Thompson says they were bought at Butterfield Auctions in

2000 by a woman who wanted to make sure they would find a good museum home, and

a tip from a friend made it possible for the Big Horn County man to buy them and

bring them to the local battlefield where Crazy Horse was instrumental in

Custer’s demise on June 25, 1876.

“I think it’s important that it’s in Big Horn

County,” offers Thompson. “We can even move it around (such as to Uncle

Sam’s Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument) for a time.”

The curator figures the controversy over the image will

make the tintype all the more a focus of curiosity for history buffs and a

drawing card for tourist interest and visitation. He plans to have posters and

postcards of the image available for sale by this year’s June 25 anniversary

at the museum’s shop and his Custer Battlefield.Trading Post & Café at

Crow Agency.

For Abiuso, it’s an amateur detective’s dream come true, “one of the things I want to finish in life.”

Over the years, he made seven trips to Montana, the

Dakotas, Nebraska and Wyoming, spending a great deal of time to study all

available museum and archival data for evidence about Crazy Horse’s

appearance, clothing, personal articles and telltale facial scar from a bullet

wound.

He can take you through the fine details about the figure

in the tintype and show how they match historical descriptions about Crazy

Horse.

“These are all descriptions by his friends who knew and

survived him,” Abiuso asserts. “His

personal medicine with the two eagle feathers and his scar – they are the main

proofs.”

Much of the testimonial comes from Chips, the medicine man

to whom Crazy Horse turned for his battle medicine, and is included in the Judge

Eli Ricker collection at Nebraska State Historical Society archives.

Chips described the chief’s medicine as including two

bilateral and matched tail feathers of the spotted eagle and how one was worn

upside down in his loose, light hair while the other was laced to a rawhide skin

that covered a black stone at the end of Crazy Horse’s medicine lanyard

hanging over the bottom of his shirt.

“That’s exactly the way the tintype looks,” notes

Abiuso, who observes each warrior’s medicine to protect them in battle was

unique to them.

“It’s very important – the eagle feathers,” he

notes. “He was the only one with his bag of medicine.”

As for the other main proof, although nay sayers for years have said they don’t see a scar, the modern technological capabilities of high-resolution scanning have brought it into an undeniable focus, the sleuth says.

At age 26, Crazy Horse had woman trouble, stealing Black

Buffalo Woman from husband No Water, who wasn’t about to let it go.

No Water borrowed a small-caliber hand-hidden pistol, apparently loaded

with only a half-charge unbeknownst to the plotter.

When he discharged it at Crazy Horse’s face, the ball

entered on the left side below his nose, following a path along the facial bone

too high to knock out any teeth, and exited ahead of his ear.

“It’s exactly that in the picture,” Abiuso

proclaims.He describes the aftermath of the shooting:

“As time passed, the wound caused a slight ‘disdainful’ ridge along

the cheek and a whitened area starting below the nostril and progressing outward

and downward in the ‘smile’ crease of the face. The point of entry is

visible as a small indent in the middle of this whitened area.”

The scar left no prominent marks on his already light complexion (his reputation was as “the light-skinned warrior”).

“Chips, in his interview with Judge Ricker, stated that

the wound did not change the color of Crazy Horse’s complexion,” points out

Abiuso. “Mari Sandoz stated the same thing in a letter to the Nebraska State

Historical Society.”

He concedes it’s understandable critics could not see the

scar in the small tintype or earlier reproductions but that’s it’s

discernible now, in an enlarged image of the face in a high-resolution scanned

photograph by Scott Burgan of Sheridan, Wyo.

More confusion stems from tintypes being positive prints,

the same way a person looks at himself in the mirror and sees his right arm as

if it were his left arm reflecting back. That’s reverse from modern

photography, where you see your right arm on the left side in a picture staring

back.

So, while it appears Crazy Horse is holding his prized red

blanket over his right arm in the tintype, he really had it over his left arm,

the same side as the scar starting above his lip. A critic seeing no scar on the

right side in the tintype would be forgetting it is not a modern photograph

where subjects are flipped laterally as they go from negative to positive.

On the Internet, the image can be viewed both as the

original mirror-image tintype and also in a linked enlargement laterally flipped

to present it in the more-familiar orientation of today, with colorization using

latest computer techniques and months of forensic research to present a true

image, says the web site (www.stringofbeads.com)

of Richard Jepperson of West Jordan, Utah, who died very recently. His nephew,

Doug Jepperson, continues to work with Thompson on designing the planned poster

and postcard.

From eyewitness descriptions, it’s known Crazy Horse was

five feet, eight inches, tall, lithe and sinewy of body, with a lean face and

thin, sharp nose. He carried a quiet dignity with a countenance described as

morose as well as dogged. He

typically wore a white muslin shirt and dark blue cloth leggings, both unusual

attire for Indians of his period, but clearly showing in the tintype.

Abiuso says he was wearing the same white cotton jersey

when he was killed.

The researcher also attaches importance that the warrior in

the image is light-skinned and had unusually loose-hanging hair, with the single

feather dangling, as well as his long braids being wrapped in otter fur almost

the color of his hair – all as did Crazy Horse.

Even if penetrating in his gaze, the Indian in the image is

in what would be regarded as a peace pose, without the full battle dress and

fierce look while holding a favorite weapon that chiefs usually brought to a

photo opportunity. Abiuso sees this as further proof the man is Crazy Horse.

“You know what’s missing (?) – the war bonnet,” he

asserts. “He was forbidden to wear one in his vision, when he was 16. That’s

another reason you can tell it was him.”

The chief also is holding in the image his favored

chief’s blanket that he got in 1867. Abiuso notes he would make sure his

blanket would be properly presented, touching perfectly to the floor, in

agreeing to have his picture taken. Mari

Sandoz also referred to Crazy Horse carrying his red blanket folded over his arm

as he walked unwittingly to the guardhouse, where he was bayoneted.

Even though fatally wounded Crazy Horse is part of the

mystery mystique that clings to the chief and many Old West happenings. Some

accounts refer to an infantry captain named Kennington.

The late Jepperson notes historians have written hundreds of pages about

his killing and that it was an event closely witnessed by “perhaps” 50

individuals.

“Yet, in the final analysis, the reader is left to draw

his or her own conclusions on the actual identity of the perpetrator of the

deed,” he observed. “While it is commonly agreed that Private William

Gentles is that person, the most definitive eyewitness accounts draw no such

conclusion..”

Gentles, a 22-year military veteran, only survived Crazy

Horse by about nine months, when “asthma” at Camp Douglas, Utah Territory,

got him.

A letter written many years later (1927) by Dr.

McGillycuddy describes Kennington escorting Crazy Horse to the guard house, a

howl from the chief as he jumped out the door again and a pass at Kennington

with the chief’s long knife. As Kennington and Little Big Man caught hold of

him, Crazy Horse slashed the Indian across one wrist, freeing himself, only to

find a double guard of 20 men close around him with fixed bayonets.

“He lunged from side to side, trying to break through,

when suddenly one of the guards (Gentles) made a lunge, and Crazy Horse fell to

the ground,” wrote the doctor, who found a bayonet wound above the hip as the

chief frothed at the mouth and said, “You have hurt me enough, my friends, it

is done.”

He relates seven-foot-tall Touch The Clouds picking up the

chief like a child and taking him to the doctor’s office, where he was laid on

his desk that McGillycuddy covered with Crazy Horse’s red blanket.

He jabbed the chief with a shot of morphine.

Old Crazy Horse, his father, came to stay in the office with a handful of

people, and near midnight the chief whispered to his father, just before he

died, “Tell the people it is no use to depend on me anymore.”

Another Indian present, Chief He Dog, left an account that

Crazy Horse was inflicted with two wounds, one on the left side of his back and

a smaller, deeper wound a little below it. He apparently left no identification

of who inflicted the wounds but said the chief jerked free of the lunge and that

Gentles missed, his bayonet going into the jailhouse door jamb.

“You can see the slashes in the wood,” offered He Dog.

The official Army position couched the death as an

accident, that Gentles pointed his bayoneted rifle at Crazy Horse to force him

back to the jail, with the chief falling on the blade in a struggle.

Crazy Horse was Minniconjou by blood heritage though raised

among the Oglala. The elder Crazy

Horse, who named his son after youthful bravery in battle, was Oglala and

Minneconjou, while his mother, Rattle Blanket Woman, was Minneconjou. Severe

mental depression caused by death of a relative apparently led her to suicide in

1844. And Crazy Horse’s Brule stepmother, Red Leggins, was the woman he

referred to as “mother.”

Crazy Horse was a major leader in a number of strikes

against the invading whites, including leading the Oglalas in the 1886 massacre

of Captain William Fetterman and 81 officers and men outside of Fort Phil Kearny

in Wyoming.

When Sioux Chief Red Cloud signed the Treaty of 1868 that

terminated that fort and two others, closing the Bozeman Trail, Crazy Horse was

one of the two principal chiefs who never accepted the deal.

He hooked up with the Uncpapa Sioux and the great medicine man Sitting

Bull and was a leader of the hostiles who declined to stay on reservations for

lifestyles designed by the whites.

When Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull and their warriors were on

their way to the great encampment on the Little Bighorn in 1876, the punitive

expedition of General George Crook ran into them in a surprise encounter that

blossomed into the no-clear-victor Battle of the Rosebud.

Days later came the Big Fight on the Greasy Grass, as the

Indians call it. The hostiles

apparently were aware of the approaching Custer force, although they may have

been surprised by the diversion provided by the Major Marcus Reno detachment

coming from the south along the river.

Crow King led several hundred of his fellow-Sioux across the river up the gully to the south soon after Custer’s command was seen on the bluffs. But the main body of the Oglalas and Cheyennes moved downstream until they reached a ford near the Cheyenne camp circle.

“(They) were led by the fanatical Crazy Horse – the

‘Stonewall Jackson of the Sioux’ – who apparently had started for Reno’s

fight and then turned about, rushing down the valley through the comparatively

small numbers of warriors riding upstream, calling out, ‘Today is a good day

to fight, today is a good day to die: cowards to the rear, brave hearts follow

me,’” Edgar Stewart reported in his 1955-published “Custer’s Luck.”

The chief moved his warriors across the river and up a long

coulee going east until it passes Battle Ridge, following it to the right and

then a southerly direction around to the east and southeast, meeting the coulee

up which Crow King’s band had traveled. Another group followed Crazy Horse but

turned southward to a position between the ridge and river, presently the site

of the battlefield cemetery. Others crossed and moved up various ravines and

gullies so that Custer’s soldiers could be attacked from all directions.

As the battle developed, a flanking move by Crazy Horse’s

hostiles was thought to have made impossible any further advance by Custer and

his surviving men toward the top of the ridge, as “the troopers prepared to

sell their lives as dearly as possible,” wrote Stewart.

After his murder, Crazy Horse was given the traditional

tree-scaffold burial on Beaver Creek, a short distance from Fort Robinson.

Sioux traditionalists still go there to pray and smoke their pipes. All

that’s left of the heroic Crazy Horse are the historical descriptions of his

contemporaries and apparently a sole tintype that matches the descriptions, now

at home at the famed battlefield.

Curator Thompson says its unveiling at the museum will be

only a first step. He sees

possibilities for further studies focusing on the debates over the tintype.

“We might even do a seminar on it,” he offers.

Thompson recalls his first chilling moment after obtaining

the portrait – the time he showed it to his friends, Oglala Sioux artist Ed

Two Bulls and his wife, Lovey, descendants of the great chief.

He says he figured they would be quite dubious about the

tintype being Crazy Horse. First engaging them in conversation, he asked what

they thought about the story that the chief was afraid of what cameras might do

to him and thus rejected ever having a photograph taken.

“He wasn’t scared of a camera. He wasn’t scared of anything, “ the curator reports the

couple told him.

Then, Thompson drew the treasured portrait from its

protective sleeve and showed it to them.

“It’s him! It’s him!” he says

they both exclaimed.

“That’s

the first time the hair stood up on my neck,” Thompson relates.

Stare into the tintype’s riveting, penetrating eyes, and make your own determination if it is Crazy Horse who has bridged more than a century to bring you the murderous chill you feel.